While this is mostly true, there is one place on the planet that is vast, empty, and even partially unclaimed: Antarctica. Today’s map, originally created by the CIA World Factbook, visualizes the active claims on Antarctic territory, as well as the location of many permanent research facilities.

The History of Antarctic Territorial Claims

In the first half of the 20th Century, a number of countries began to claim wedge-shaped portions of territory on the southernmost continent. Even Nazi Germany was in on the action, claiming a large swath of land which they dubbed New Swabia. After WWII, the Antarctic Treaty system—which established the legal framework for the management of the continent—began to take shape. In the 1950s, seven countries including Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway, and the United Kingdom claimed territorial sovereignty over portions of Antarctica. A number of other nations, including the U.S. and Japan, were engaged in exploration but hadn’t put forward claims in an official capacity. Despite the remoteness and inhospitable climate of Antarctica, the idea of claiming such large areas of landmass has proven appealing to countries. Even the smallest claim on the continent is equivalent to the size of Iraq. A few of the above claims overlap, as is the case on the Antarctic Peninsula, which juts out geographically from the rest of the continent. This area is less remote with a milder climate, and is subject to claims by Argentina, Chile, and the United Kingdom (which governs the nearby Falkland Islands). Interestingly, there is still a large portion of Antarctica that remains unclaimed today. Just east of the Ross Ice Shelf lies Marie Byrd Land, a vast, remote territory that is by far the largest unclaimed land area on Earth. While Antarctica has no official government, it is administered through yearly meetings known as the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meetings. These meetings involve a number of stakeholders, from member nations to observer organizations.

Frontage Theory: Another Way to Slice it

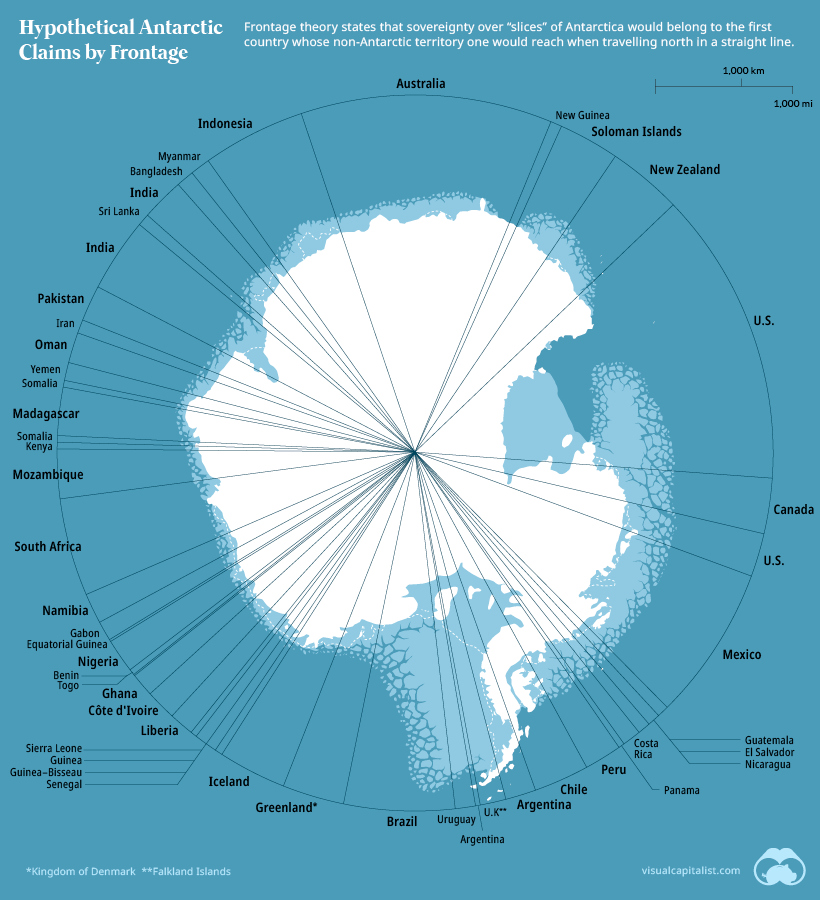

Of course, critics could argue that current claims are arbitrary, and that there is a more equitable way to partition land in Antarctica. That’s where Frontage Theory comes in. Originally proposed by Brazilian geopolitical scholar Therezinha de Castro, the theory argues that sectors of the Antarctic continent should be distributed according to meridians (the imaginary lines running north–south around the earth). Wherever straight lines running north hit landfall, that country would have sovereignty over the corresponding “wedge” of Antarctic territory. The map below shows roughly how territorial claims would look under that scenario.

While Brazil has obvious reasons for favoring this solution, it’s also a thought experiment that produces an interesting mix of territorial claims. Not only do nearby countries in Africa and South America get a piece of the pie, but places like Canada and Greenland would end up with territory adjacent to both of the planet’s poles.

Leaving the Pie Unsliced

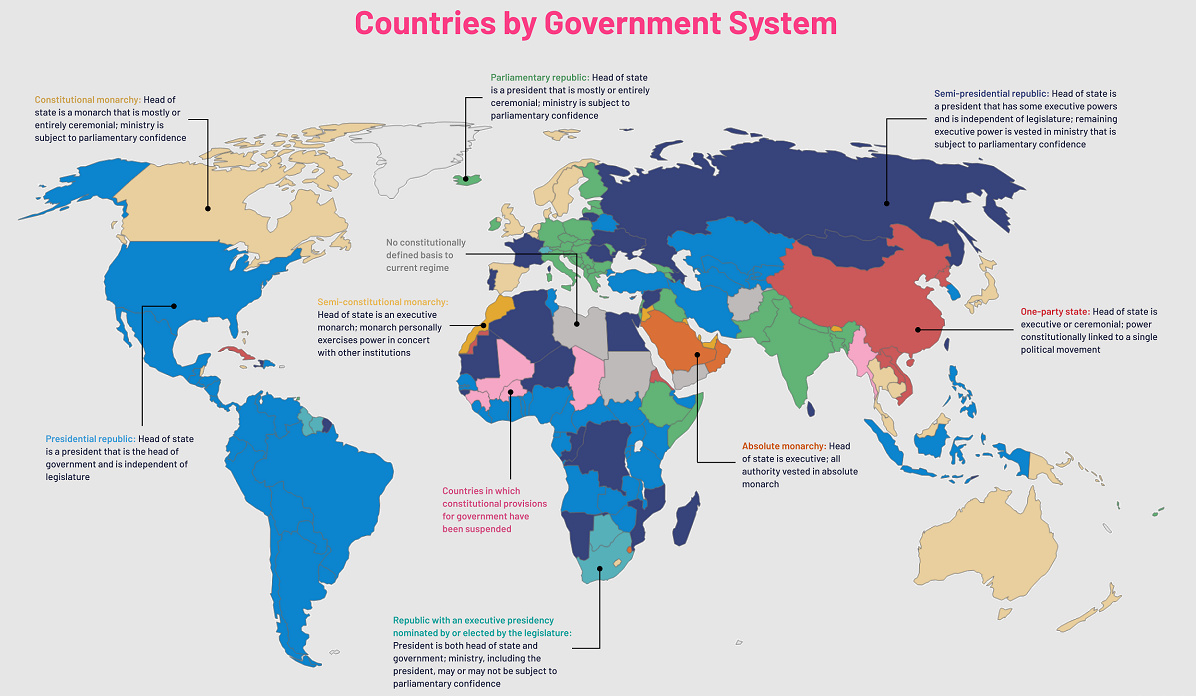

Thanks to the Antarctic Treaty, there is no mining taking place in Antarctica, and thus far no country has set up a permanent settlement on the continent. Aside from scattered research stations and a few thousand researchers, claims in the region have a limited impact. For the near future at least, the slicing of the Antarctic pie is only hypothetical. on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.