The idea of UBI as a means to both combat poverty and improve economic prospects has been around for decades. With the COVID-19 pandemic wreaking havoc on economies worldwide, momentum behind the idea has seen a resurgence among certain groups. Of course, the money to fund basic income programs has to come from somewhere. UBI relies heavily on government budgets or direct funding to cover the regular payments. As policymakers examine this trade-off between government spending and the potential benefits, there is a growing pool of data to draw inferences from. In fact, basic income has been piloted and experimented on all around the world—but with a mixed bag of results.

What Makes Basic Income Universal?

UBI operates by giving people the means to meet basic necessities with a regular stipend. In theory, this leaves them free to spend their money and resources on economic goods, or searching for better employment options. Before examining the programs, it’s important to make a distinction between basic income and universal basic income.

With these parameters in mind, and thanks to data from the Stanford Basic Income Lab, we’ve mapped 48 basic income programs that demonstrate multiple features of UBI and are regularly cited in basic income policy. Some mapped programs are past experiments used to evaluate basic income. Others are ongoing or new pilots, including recently launched programs in Germany and Spain. Recently, Canada joined the list as countries considering UBI as a top policy priority in a post-COVID world. But as past experiments show, ideas around basic income can be implemented in many different ways.

Basic Income Programs Took Many Forms

Basic income pilots have seen many iterations across the globe. Many paid out in U.S. dollars, while others chose to stick with local currencies (marked by an asterisk for estimated USD value). Many of the programs meet the classical requirements of UBI. Of the 48 basic income programs tallied above, 75% paid out monthly, and 60% were paid out to individuals. However, for various reasons, not all of these programs follow UBI requirements. For example, 38% of the basic income programs were paid out to households instead of individuals, and many programs have paid out in lump sums or over varying time frames. Interestingly, the need for better understanding of basic income has resulted in many divergences between programs. Some programs were only targeted at specific groups like South Korea’s Basic Income for Farmers program, while others like the Baby’s First Years program in the U.S. have been experimenting with different dollar amounts in order to evaluate efficiency. Other experiments based payments made off of the total income of recipients. For example, in the U.S., the Rural Income and New Jersey Income Maintenance Experiments paid out using a negative income tax (return) on earnings, while recipients of Canada’s Ontario Basic Income Pilot received fixed amounts minus 50% of their earned income.

Varying Programs with Varied Results

So is basic income the real deal or a pipe dream? The results are still unclear. Some, like the initial pilots for Uganda’s Eight program, were found to result in significant multipliers on economic activity and well-being. Other programs, however, returned mixed results that made further experimentation difficult. Finland’s highly-touted pilot program decreased stress levels of recipients across the board, but didn’t positively impact work activity. The biggest difficulty has been in keeping programs going and securing funding. Ontario’s three-year projects were prematurely cancelled in 2018 before they could be completed and assessed, and the next stages of Finland’s program are in limbo. Likewise in the U.S., start-up incubator Y Combinator has been planning a $60M basic income study program, but can’t proceed until funding is secured.

A Post-COVID Future for UBI?

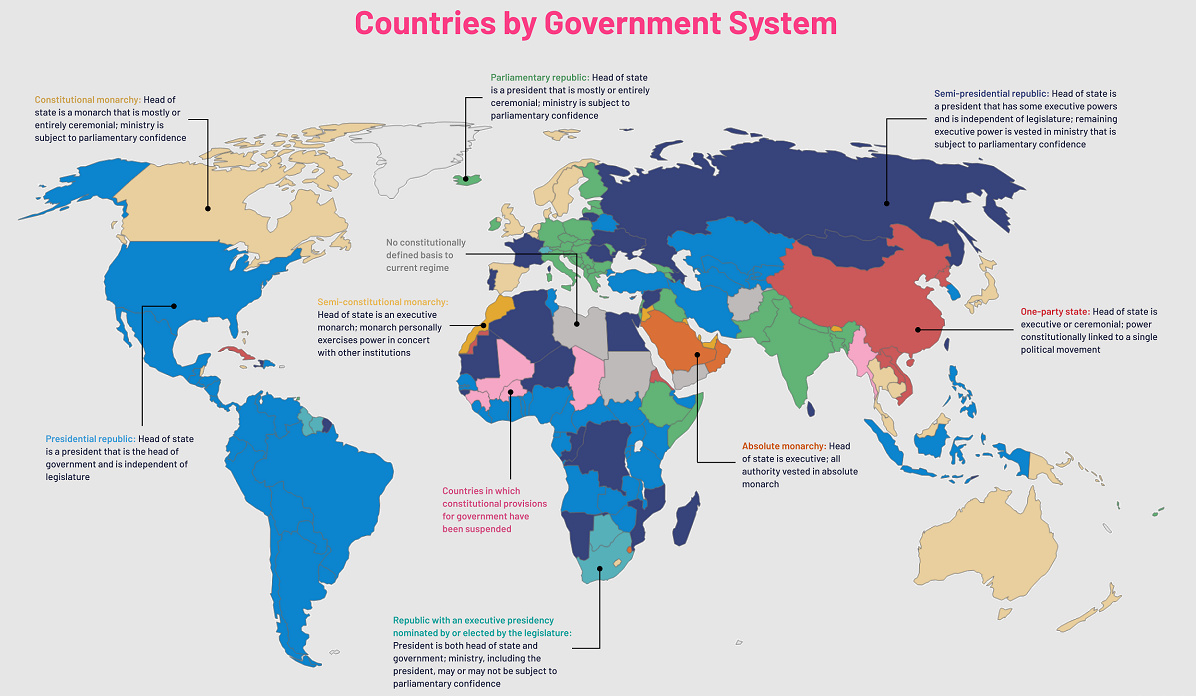

In light of COVID-19, basic income has once again taken center stage. Many countries have already implemented payment schemes or boosted unemployment benefits in reaction to the pandemic. Others like Spain have used that momentum to launch fully-fledged basic income pilots. It’s still too early to tell if UBI will live up to expectations or if the idea will fizzle out, but as new experiments and policy programs take shape, a growing amount of data will become available for policymakers to evaluate. on Even while political regimes across these countries have changed over time, they’ve largely followed a few different types of governance. Today, every country can ultimately be classified into just nine broad forms of government systems. This map by Truman Du uses information from Wikipedia to map the government systems that rule the world today.

Countries By Type of Government

It’s important to note that this map charts government systems according to each country’s legal framework. Many countries have constitutions stating their de jure or legally recognized system of government, but their de facto or realized form of governance may be quite different. Here is a list of the stated government system of UN member states and observers as of January 2023: Let’s take a closer look at some of these systems.

Monarchies

Brought back into the spotlight after the death of Queen Elizabeth II of England in September 2022, this form of government has a single ruler. They carry titles from king and queen to sultan or emperor, and their government systems can be further divided into three modern types: constitutional, semi-constitutional, and absolute. A constitutional monarchy sees the monarch act as head of state within the parameters of a constitution, giving them little to no real power. For example, King Charles III is the head of 15 Commonwealth nations including Canada and Australia. However, each has their own head of government. On the other hand, a semi-constitutional monarchy lets the monarch or ruling royal family retain substantial political powers, as is the case in Jordan and Morocco. However, their monarchs still rule the country according to a democratic constitution and in concert with other institutions. Finally, an absolute monarchy is most like the monarchies of old, where the ruler has full power over governance, with modern examples including Saudi Arabia and Vatican City.

Republics

Unlike monarchies, the people hold the power in a republic government system, directly electing representatives to form government. Again, there are multiple types of modern republic governments: presidential, semi-presidential, and parliamentary. The presidential republic could be considered a direct progression from monarchies. This system has a strong and independent chief executive with extensive powers when it comes to domestic affairs and foreign policy. An example of this is the United States, where the President is both the head of state and the head of government. In a semi-presidential republic, the president is the head of state and has some executive powers that are independent of the legislature. However, the prime minister (or chancellor or equivalent title) is the head of government, responsible to the legislature along with the cabinet. Russia is a classic example of this type of government. The last type of republic system is parliamentary. In this system, the president is a figurehead, while the head of government holds real power and is validated by and accountable to the parliament. This type of system can be seen in Germany, Italy, and India and is akin to constitutional monarchies. It’s also important to point out that some parliamentary republic systems operate slightly differently. For example in South Africa, the president is both the head of state and government, but is elected directly by the legislature. This leaves them (and their ministries) potentially subject to parliamentary confidence.

One-Party State

Many of the systems above involve multiple political parties vying to rule and govern their respective countries. In a one-party state, also called a single-party state or single-party system, only one political party has the right to form government. All other political parties are either outlawed or only allowed limited participation in elections. In this system, a country’s head of state and head of government can be executive or ceremonial but political power is constitutionally linked to a single political movement. China is the most well-known example of this government system, with the General Secretary of the Communist Party of China ruling as the de facto leader since 1989.

Provisional

The final form of government is a provisional government formed as an interim or transitional government. In this system, an emergency governmental body is created to manage political transitions after the collapse of a government, or when a new state is formed. Often these evolve into fully constitutionalized systems, but sometimes they hold power for longer than expected. Some examples of countries that are considered provisional include Libya, Burkina Faso, and Chad.