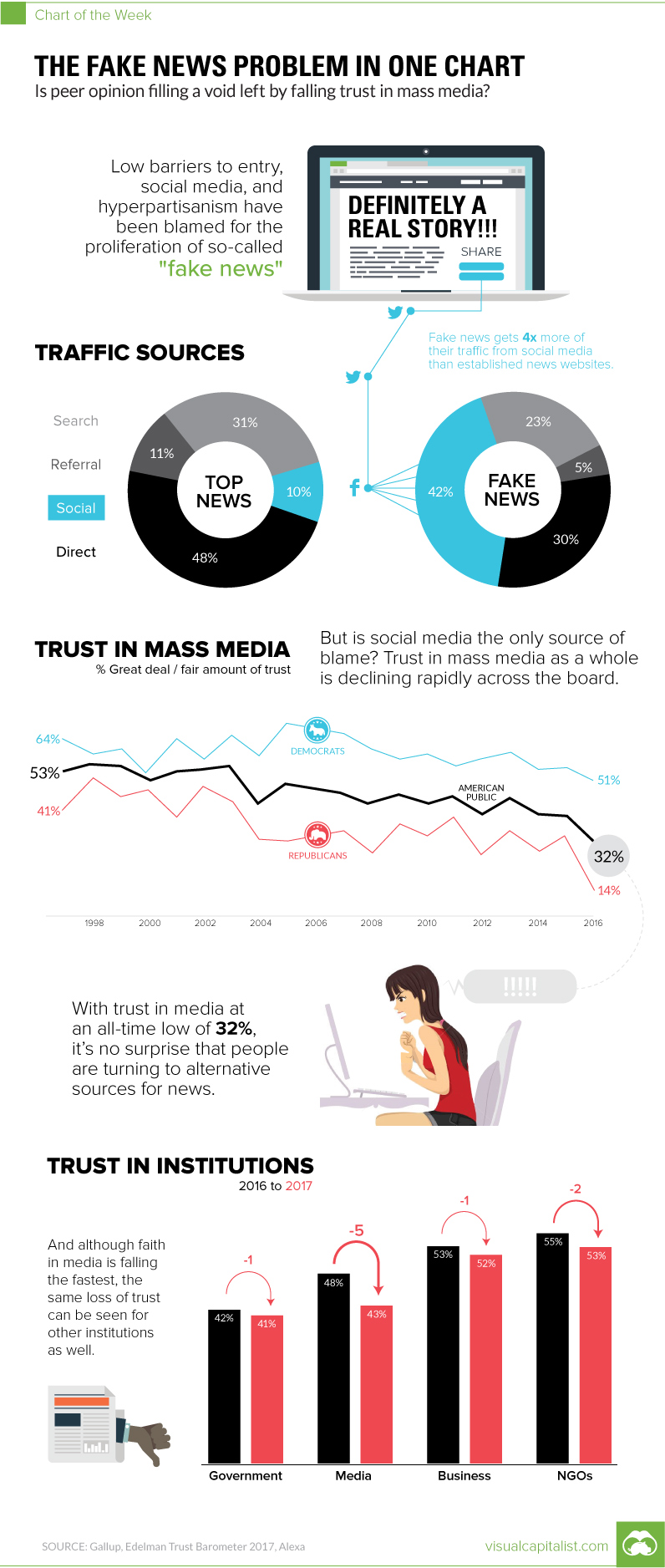

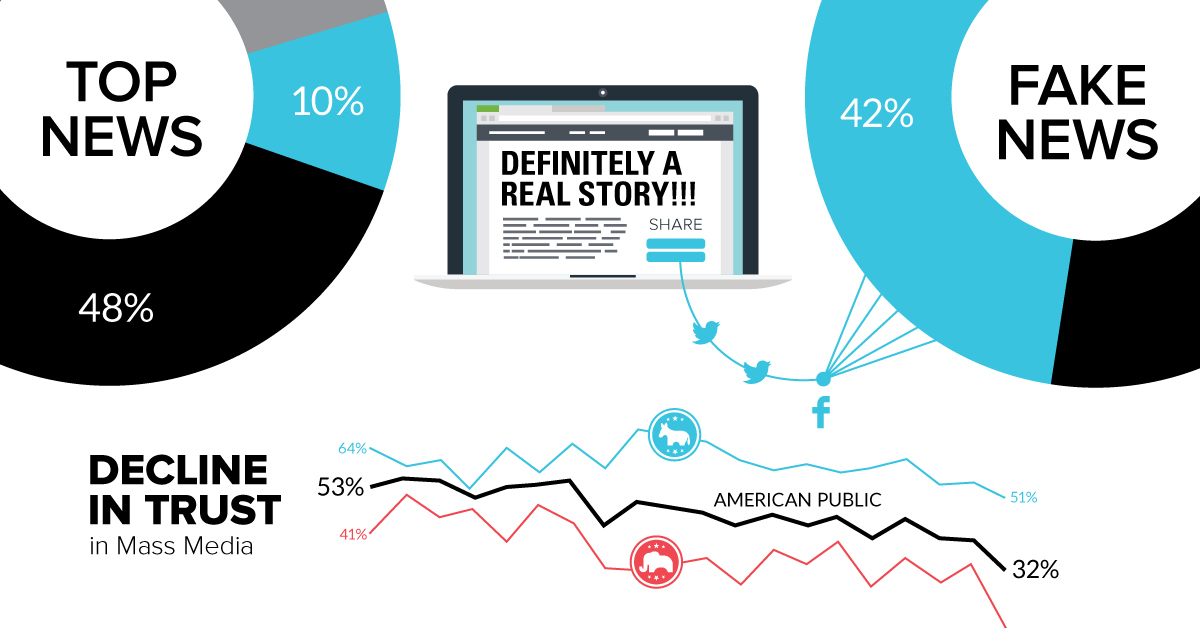

Chart: The Fake News Problem

Peer opinion fills a void left by falling trust in mass media

The Chart of the Week is a weekly Visual Capitalist feature on Fridays. There’s been no shortage of blame passed around for the so-called “fake news” epidemic that has been front and center since the U.S. election. Social media has been singled out as one key factor leading to the spread of misleading or false news. However, low barriers to entry for creating content, hyperpartisanism, confirmation bias, and the echo-chamber effect have also been identified as causes or symptoms in the proliferation of such stories. It’s certainly a complex problem to unravel, and many proposed solutions are just as alarming as the symptoms they try to treat. The decentralization and fragmentation of information is the core of what makes the internet great, and this democratization helps to decouple power away from the established institutions that may or may not have our interests at heart. How do we regulate news for its authority and legitimacy without stifling alternate viewpoints, differing narratives, and independent sources of information?

Root Causes

In today’s landscape, people are turning away from traditional media and gravitating towards digital content. In this new digital media paradigm, who is considered a trustworthy and convenient source of information? As long as they could remain reputable, the mainstream outlets that garnered eyeballs throughout broadcasting history should have been the obvious benefactors of this transition. Groups like CNN and Fox News, or The New York Times and The Washington Post, could have remained unquestioned authorities on the issues. However, it seems like this opportunity has been recently squandered to some extent. These outlets have been slow to adopt their business strategies to the digital landscape, and they remain in damage control mode as advertising revenues drop and profitability wanes. Publishers have been under immense pressure to generate views, and have taken shortcuts in content creation to do this. Hyperpartisan viewpoints that confirm existing biases (aka, the Huffington Post or Breitbart models) and sensational clickbait headlines have been one easy way to build traffic. Some publishers also have an itchy trigger finger, and it seems that getting a story out first has become more important than verifying its validity. These above factors have, ironically, led to mass media as being a direct part of the “fake news” problem. The retracted stories on Russian propaganda by the Washington Post have been a lightning rod for scrutiny, and entire posts are dedicated to keeping misleading stories from established media at bay. Having a track record with zero blemishes is obviously a difficult target to hit, but the reality is that we are seeing misleading news from everywhere now: “fake news” outlets, mainstream outlets, and the White House itself.

Falling Trust in Media and Institutions

Even before “fake news” hit the mainstream, a poll by Gallup showed that Americans’ trust in mass media was hitting an all-time low. In September 2016, only 32% of people said they have a great deal or fair amount of trust in the media, which is a decline of -8% from the previous year. A report from Edelman from January 2017 is even more damning. Trust of the media declined -5% from 2016, which is faster than trust is declining in government (-1%), business (-1%), and NGOs (-2%). As we mentioned earlier, the rise of fake news is complex and very difficult to untangle. However, the fact is that established news outlets aren’t doing themselves any favors. If people feel like they can’t trust the Washington Post or other such sources, then it should be no surprise that they are turning to the power of “word of mouth” from their peers more often – no matter how fallible this might be.

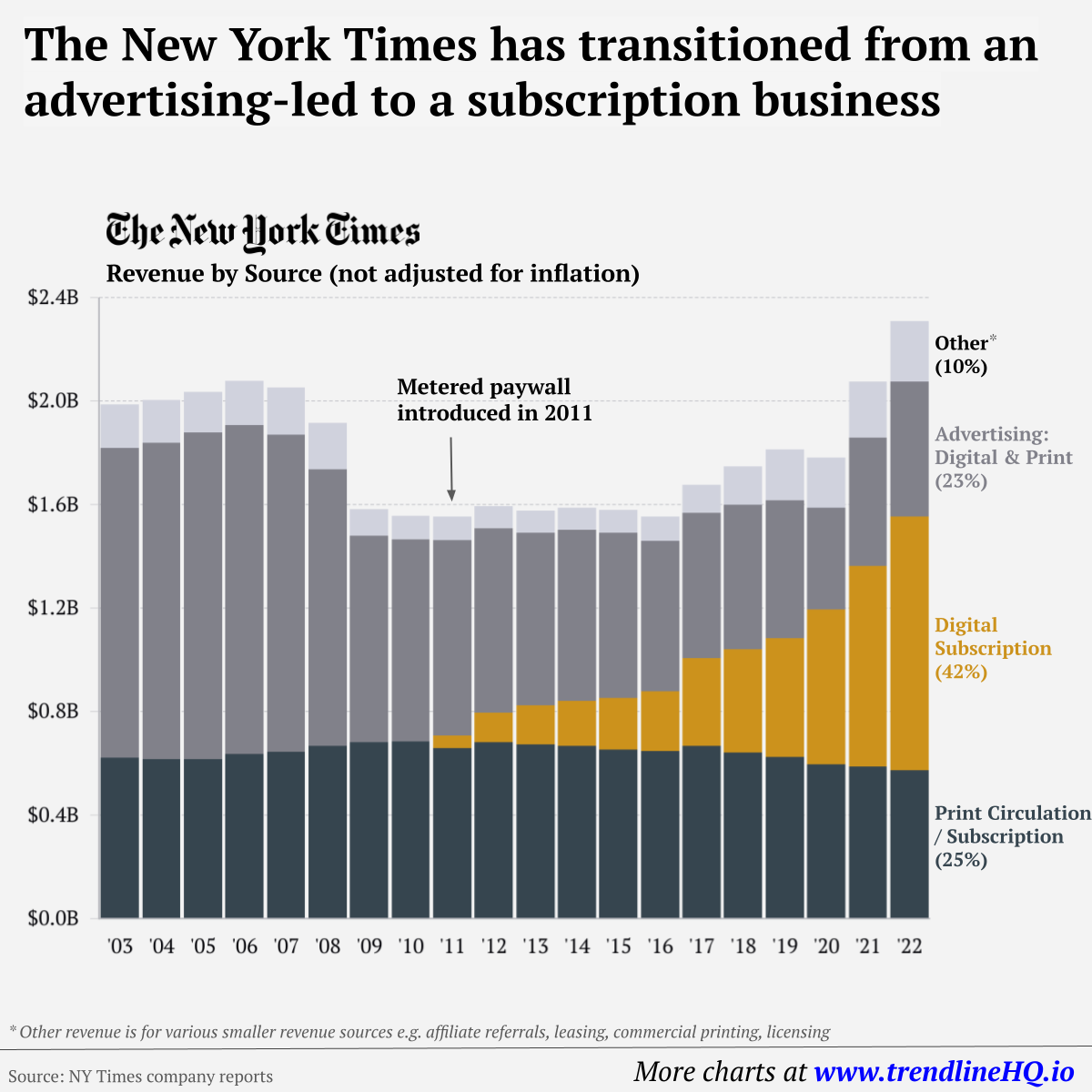

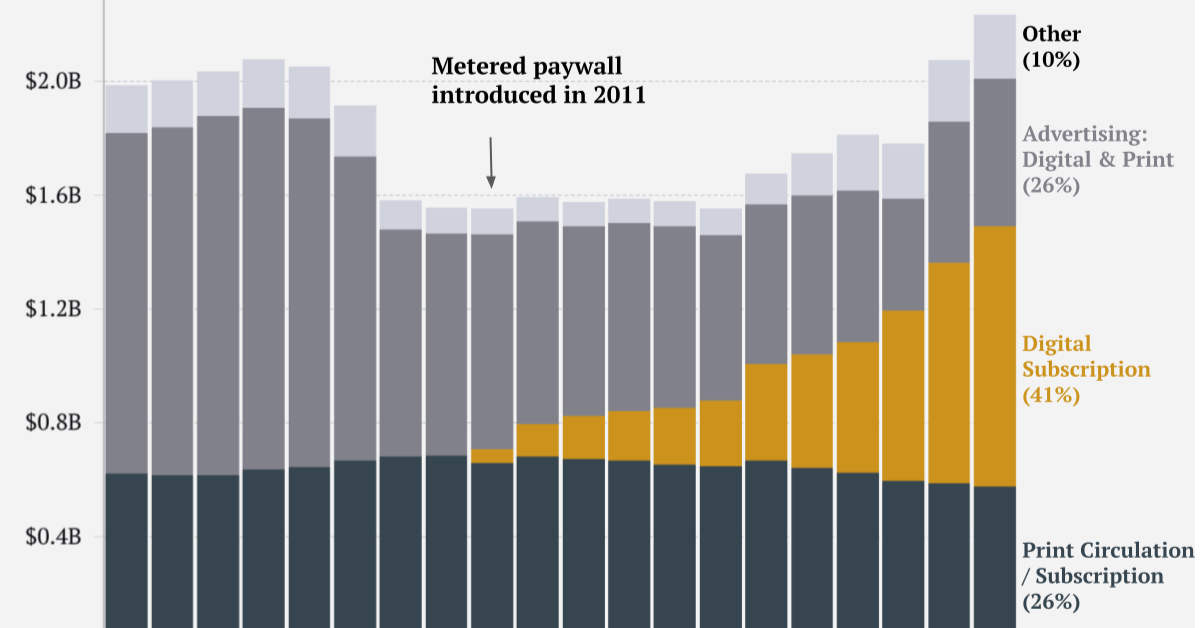

on Similar to the the precedent set by the music industry, many news outlets have also been figuring out how to transition into a paid digital monetization model. Over the past decade or so, The New York Times (NY Times)—one of the world’s most iconic and widely read news organizations—has been transforming its revenue model to fit this trend. This chart from creator Trendline uses annual reports from the The New York Times Company to visualize how this seemingly simple transition helped the organization adapt to the digital era.

The New York Times’ Revenue Transition

The NY Times has always been one of the world’s most-widely circulated papers. Before the launch of its digital subscription model, it earned half its revenue from print and online advertisements. The rest of its income came in through circulation and other avenues including licensing, referrals, commercial printing, events, and so on. But after annual revenues dropped by more than $500 million from 2006 to 2010, something had to change. In 2011, the NY Times launched its new digital subscription model and put some of its online articles behind a paywall. It bet that consumers would be willing to pay for quality content. And while it faced a rocky start, with revenue through print circulation and advertising slowly dwindling and some consumers frustrated that once-available content was now paywalled, its income through digital subscriptions began to climb. After digital subscription revenues first launched in 2011, they totaled to $47 million of revenue in their first year. By 2022 they had climbed to $979 million and accounted for 42% of total revenue.

Why Are Readers Paying for News?

More than half of U.S. adults subscribe to the news in some format. That (perhaps surprisingly) includes around four out of 10 adults under the age of 35. One of the main reasons cited for this was the consistency of publications in covering a variety of news topics. And given the NY Times’ popularity, it’s no surprise that it recently ranked as the most popular news subscription.